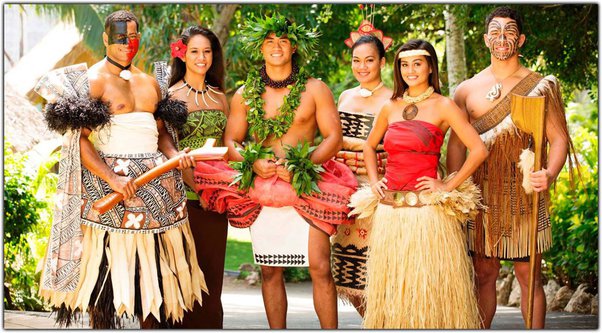

Chamorro of Guam vs. Kanaka Maoli of Hawaii

The Pacific Ocean is a vast and diverse region, home to many indigenous cultures, each with its own unique history, language, and traditions. Among these are the Chamorro people of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands, and the Kanaka Maoli, or Native Hawaiians, of Hawaii. While both groups share the commonality of being Pacific Islanders, they have distinct cultural identities, histories, and ways of life. This blog delves into the differences between the Chamorro people and the Kanaka Maoli, exploring their origins, languages, societal structures, cultural practices, and the challenges they face in the modern world.

Origins and Historical Background

Chamorro People

The Chamorro people are the indigenous inhabitants of the Mariana Islands, including Guam, Saipan, Tinian, and Rota. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Chamorro have inhabited these islands for over 4,000 years, with origins traced back to the Austronesian-speaking peoples who migrated from Southeast Asia.

The Chamorro society was traditionally organized into matrilineal clans, and they were known for their maritime skills, particularly in navigation and outrigger canoe building. The Chamorro were also skilled in agriculture and fishing, living in villages that were typically located near the coast.

In 1521, the Chamorro people first encountered Europeans when Ferdinand Magellan arrived in Guam. This marked the beginning of significant changes to Chamorro society, as the Spanish colonized the Marianas in the 17th century. The Spanish imposed Catholicism, altered the social structure, and introduced new crops and animals. The Chamorro population suffered greatly from introduced diseases and conflicts with the Spanish, leading to a dramatic decline in their numbers.

Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians)

The Kanaka Maoli, or Native Hawaiians, are the indigenous people of the Hawaiian Islands. They are believed to have arrived in Hawaii around 1,500 years ago, originating from Polynesian voyagers who navigated across the vast Pacific Ocean from the Marquesas Islands and later from Tahiti. These skilled navigators brought with them a complex society, complete with a rich oral tradition, sophisticated agricultural systems, and deep spiritual beliefs.

Hawaiian society was organized into a strict social hierarchy, with the aliʻi (chiefs) ruling over the land and its people. The kapu system, a set of religious laws, governed every aspect of life, from food preparation to social interactions. The Kanaka Maoli developed advanced agricultural techniques, including the construction of fishponds and terraced taro fields, which allowed them to sustain a growing population.

The arrival of Captain James Cook in 1778 marked the beginning of significant changes for the Kanaka Maoli. The introduction of Western diseases, firearms, and new religions, combined with the eventual colonization by the United States, led to dramatic shifts in Hawaiian society. The overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 and subsequent annexation by the United States in 1898 further eroded the cultural and political sovereignty of the Kanaka Maoli.

Language and Oral Traditions of Chamorro and Kanaka Maoli

Chamorro Language

The Chamorro language, known as “Fino’ Chamoru,” is an Austronesian language that has been heavily influenced by Spanish due to over three centuries of Spanish colonization. Chamorro was once the dominant language in the Mariana Islands, but today, it is considered endangered, with many younger Chamorros speaking English as their first language. Efforts are being made to revitalize the language, including the incorporation of Chamorro language classes in schools and the use of Chamorro in media and public signage.

The Chamorro language is rich in proverbs, oral histories, and traditional chants that convey the values, beliefs, and history of the Chamorro people. These oral traditions are crucial for preserving the Chamorro identity and passing down cultural knowledge from one generation to the next.

Hawaiian Language

The Hawaiian language, or “ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi,” is a Polynesian language closely related to other languages in the Pacific, such as Tahitian and Māori. Before Western contact, Hawaiian was the primary language spoken throughout the Hawaiian Islands, with a rich tradition of chant (oli) and storytelling (moʻolelo) that conveyed the history, genealogy, and spirituality of the Kanaka Maoli.

However, the Hawaiian language faced severe decline following the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the imposition of English as the dominant language in schools and government. By the mid-20th century, ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi was on the brink of extinction, with only a few native speakers remaining.

In recent decades, there has been a significant resurgence of interest in revitalizing the Hawaiian language. The establishment of Hawaiian language immersion schools, the creation of Hawaiian language media, and the recognition of Hawaiian as an official state language have all contributed to the revival of ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi. Today, the Hawaiian language is taught in schools across the islands, and many young Kanaka Maoli are reclaiming their linguistic heritage.

Social Structure and Governance

Chamorro Society

Traditional Chamorro society was organized into matrilineal clans, with lineage traced through the mother’s side. The society was divided into two main classes: the matua (upper class) and the manachang (lower class). The matua were the landowners and leaders, while the manachang were often laborers and fishermen. The Chamorro also had a caste of skilled navigators known as maga’lahi (chiefs) and maga’håga (female chiefs), who played crucial roles in the community.

Spanish colonization brought significant changes to Chamorro society. The introduction of Catholicism and Spanish governance disrupted the traditional social structure, with the Spanish imposing their own hierarchical system. Over time, the Chamorro people adapted to these changes, blending elements of their indigenous culture with Spanish customs.

Today, Chamorro society is a blend of indigenous and Western influences, with a strong emphasis on family (familiå), respect for elders (manåmko’), and community cooperation (inafa’maolek). The Chamorro people continue to practice traditional customs, such as respect for ancestral spirits (taotao mo’na) and the preparation of traditional foods during fiestas and other celebrations.

Kanaka Maoli Society

Kanaka Maoli society was traditionally organized into a hierarchical system, with the aliʻi (chiefs) at the top, followed by the kahuna (priests and experts), the makaʻāinana (commoners), and the kauwā (outcasts or slaves). The aliʻi held power over the land and its resources, and their authority was reinforced by the kapu system, a complex set of religious laws that governed every aspect of life.

The kapu system dictated social interactions, resource management, and religious practices, ensuring that the Kanaka Maoli lived in harmony with the land (ʻāina) and the gods (akua). The aliʻi were believed to be descended from the gods, and their rule was considered divinely sanctioned.

The arrival of Europeans and Americans in Hawaii brought significant changes to Kanaka Maoli society. The introduction of Christianity, the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and the imposition of Western laws led to the dismantling of the kapu system and the loss of traditional governance structures. However, the Kanaka Maoli have continued to assert their cultural and political identity, advocating for the restoration of Hawaiian sovereignty and the protection of their land and resources.

Cultural Practices and Beliefs

Chamorro Cultural Practices

Chamorro culture is deeply rooted in the concept of inafa’maolek, which translates to “making it good for everyone” or “harmony.” This principle emphasizes the importance of community, cooperation, and mutual respect. Chamorro cultural practices often revolve around family and community gatherings, such as fiestas, where traditional foods like kelaguen, red rice, and empanada are prepared and shared.

Respect for ancestors and the land is also a central aspect of Chamorro culture. The Chamorro people believe in the presence of ancestral spirits, known as taotao mo’na, who inhabit the land and must be respected and honored. Traditional practices such as chant (kantan chamorrita), storytelling, and the creation of crafts like woven mats and pottery are ways in which the Chamorro people maintain a connection to their heritage.

Catholicism plays a significant role in Chamorro culture, with religious practices often blending indigenous beliefs with Christian traditions. Many Chamorro celebrations, such as the annual fiesta in honor of a village’s patron saint, reflect this fusion of Catholic and indigenous customs.

Kanaka Maoli Cultural Practices

Kanaka Maoli culture is deeply connected to the land (ʻāina), the ocean, and the gods (akua). Traditional practices such as hula (dance), oli (chant), and the creation of lei (garlands) are not only expressions of art but also ways of transmitting knowledge, genealogy, and spiritual beliefs. Hula, for example, is a sacred dance that tells stories of the gods, the land, and the people, while oli serves as a means of communication with the divine.

The concept of mālama ʻāina, or caring for the land, is central to Kanaka Maoli culture. This practice reflects the belief that the land and its resources are sacred and must be protected and nurtured. Traditional Hawaiian agriculture, such as the cultivation of taro (kalo) in wetland terraces (loʻi), is a manifestation of this deep respect for the land.

The Kanaka Maoli also have a rich spiritual tradition, with gods and goddesses associated with natural elements such as the ocean, mountains, and volcanoes. The goddess Pele, for example, is revered as the deity of fire and volcanoes, and her presence is felt in the volcanic activity on the Big Island of Hawaii.

Christianity, introduced by missionaries in the 19th century, has become a significant part of Hawaiian culture, but many Kanaka Maoli

have integrated Christian beliefs with their traditional spiritual practices. This blending of faiths can be seen in the way some families honor both their Christian faith and their deep reverence for the ʻāina and akua (gods). For instance, a family might attend church services while also participating in traditional rituals to honor their ancestors or the gods associated with their land.

Modern Challenges and Cultural Revitalization

Both the Chamorro people and the Kanaka Maoli have faced considerable challenges in the modern era, largely due to colonization, cultural erosion, and the pressures of globalization. However, both groups are actively engaged in efforts to revitalize their cultures, reclaim their identities, and address contemporary issues facing their communities.

Chamorro People Today

The Chamorro people have seen their population dwindle and their culture increasingly overshadowed by American and Western influences. The U.S. military presence in Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands has also had a profound impact on the land, resources, and way of life for many Chamorros. Issues such as land ownership, environmental degradation, and the preservation of Chamorro culture and language are at the forefront of contemporary Chamorro activism.

Language revitalization is one of the most significant efforts being made to preserve Chamorro culture. Community leaders, educators, and activists are working to ensure that the Chamorro language is taught in schools and used in public spaces. Cultural festivals, traditional crafts, and oral history projects are also important components of the Chamorro cultural revival.

Additionally, there is a growing movement among Chamorro people to gain greater political autonomy and recognition of their rights as an indigenous people. This includes efforts to address issues of land rights, environmental protection, and the impact of U.S. military activities on their islands.

Kanaka Maoli Today

The Kanaka Maoli have also faced substantial challenges, particularly in the wake of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and subsequent annexation by the United States. The loss of sovereignty, land rights, and cultural identity has had lasting effects on Native Hawaiians, who continue to struggle with issues such as poverty, health disparities, and the erosion of their cultural practices.

However, the Kanaka Maoli have been at the forefront of a cultural renaissance that seeks to reclaim and revitalize Hawaiian traditions. The resurgence of the Hawaiian language is a significant achievement, with immersion schools, university programs, and community initiatives playing a critical role in its revival. Cultural practices such as hula, oli, and traditional Hawaiian navigation have also seen a resurgence, as more Kanaka Maoli seek to reconnect with their heritage.

Land rights and environmental protection are central issues for the Kanaka Maoli. Movements such as the protest against the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope on Mauna Kea reflect a broader struggle to protect sacred sites and assert Native Hawaiian sovereignty. The concept of aloha ʻāina, or love for the land, continues to guide many Kanaka Maoli in their efforts to preserve their culture and environment for future generations.

The Chamorro people and the Kanaka Maoli of Hawaii are both resilient communities with rich histories and cultural identities that have survived centuries of colonization and external pressures. While they share some similarities as indigenous peoples of the Pacific, their distinct languages, social structures, and cultural practices highlight the diversity of the region.

Today, both groups are actively engaged in efforts to preserve and revitalize their cultures, reclaim their rights, and address the challenges they face in the modern world. Through these efforts, the Chamorro and Kanaka Maoli are ensuring that their unique cultural identities will continue to thrive, providing a sense of pride and continuity for future generations.